- Home

- Shawn Speakman

Unbound Page 2

Unbound Read online

Page 2

"You haven't called me by my name, Chatar. Are you afraid to have her hear it?"

"She must decide your name for herself, as you know. What she sees is not what I see. What she hears is not what I hear. That is your gift."

"More of a curse, to be fair." The chalk snapped suddenly and fell from his fingers, and he scrabbled desperately around him for the pieces. His fingers trembled, and she saw his whole body convulse when the tiny fragments powdered in his grip. He reached out for a box next to him, and found it empty. "No. No. No."

"Allow me," Chatar Singh said. He stepped forward and crouched a few feet from the man, opened the box of chalk he held, and extended one. It was white chalk, the same color as what had broken. He placed the box down in easy reach of the captive, and then the second box, filled with blue. "We are here to be of service."

The man sobbed and snatched the fresh chalk from her father's hand, and began scribbling frantically, as if he had time to make up. After a few seconds, he breathed easier, and the rhythm slowed to a more deliberate speed. "Thank you," he said. "You are a wise man. Have you explained me to your daughter yet?"

"Only you can explain what you are."

The man laughed. It sounded weird and hollow, and she thought that it might have been angry, too. "Of course, Chatar Singh. Now that she's here, I know why you love her more than anything in this world. It explains why you named me as you did."

Her father said nothing to that. He stood up and backed away, still staring into the unfocused distance, and made a formal bow. He turned and walked back to Samarjit, and whispered, "Take him your chalk. Do not get close."

She didn't want to do this anymore. She felt sick and light-headed now, and it was hard to breathe. But she couldn't let her father see her fear, could she? He expected more of her, and she had never wanted to disappoint him. Not the way her mother had.

She walked forward and crouched down, in exactly the same spot her father had chosen. She took the top off the box and slid that offering over next to the other two her father had delivered.

Her hand was still extended when the captive turned fast as the hiss of a whip, and his fingers wrapped around her wrist. The contact burned like a bracelet of heated metal, and she cried out and tried to jerk backward, but it made no difference. No difference at all. She was not strong enough to break free.

No one could be that strong.

"Samarjit." He sounded different, so close, so soft. Her name still sounded like a prayer on his lips. "Are you afraid of death?"

She looked at him, directly into his face, into the endless black fall of his eyes, the madness of his smile. The feelings that swept over her were indescribable . . . longing, need, anguish, horror, hunger, rage, so many, so fast, so intense that she felt burned black by them.

And then she saw him. Truly saw him. Not the pretty, pretty face or the flawless skin or silken hair. Not the disguise he wore to save those who came here.

She saw the whole world dying in blood and horror and pain and fear and fire, dying and being reborn, over and over. His lips were close to her ear now, close enough that his cool breath puffed against her hair. "I am not mad. The world is mad. It must be made sane." He smelled of burning and blood.

Her father was shouting her name, and she saw from the corner of her eye that he was lunging forward with his kirpan out and ready to strike. It took only a single, sharp glance from the captive to freeze him in place, with his kirpan half raised. She could see the panic in his eyes, the struggle to be free and come to her.

The captive held tight to Sammy's right wrist, and she could no more have broken that hold than ripped away her own arm. The screaming inside her faded to a whisper—not gone, no, never gone now, but she could keep it quiet.

"What are you?" she whispered then. It sounded rational, calm, controlled. It was not. She was not.

"Name me and we will both know," he said.

"I can't!" She stared past him, at the frozen-in-place form of her father, who was breathing in short, agonized gasps. There were tears running from his eyes down his cheeks, wetting his beard. "Please let my father go," she said. "Please."

"If I let him go now, I will have to kill him. Is that what you want?"

"No!"

"Then he must stay there until you name me," the captive said. He was still writing with his left hand. He had never stopped, she realized, even as he held on to her. "What am I?"

"You're—you're a demon!"

"So speaks the Christian in you. What if I told you that this is my hell? And you are my demons?"

"I'm not!"

"Sweet Samarjit, you are exactly that to me. Demon. Master. Slaver. Monster." He smiled wider this time, and she caught her breath at the sharpness of his teeth. "All these things, you are. And so you must name me."

"Or?"

"There is no or. Name me and I let you go."

"What does my father call you?"

"That's his name. It isn't yours. If you want to live, name me!" His face twisted into something no longer beautiful, and she saw his hunger, saw how he wanted to destroy her, her father, the Citadel, the world. He was a wounded and angry creature, hobbled and helpless, and it hurt to see it.

"No," she said.

He snapped her wrist.

She screamed. It was a high, thin, shocked sound, more surprise than pain at first, but the pain came fast behind in electric waves that pulsed red behind her eyes. "Let go!"

"Name me!" he roared and twisted her arm. More bones shattered. She shrieked and cried and battered at him, and while he broke her apart, one bone at a time, his left hand continued that steady, rapid scrape of chalk on walls. "Name me and live!"

"Kaam! Your name is Kaam!"

Oddly, she didn't even feel him let go. She only knew that he had turned away to focus on his endless, steady writing, and for a moment she clutched her arm close to her chest, trembling, unable to bear to move it . . . and then she realized the pain was completely gone.

Her wrist was whole. Her bones were unbroken.

Her father grabbed her and pulled her up and away, and she realized that he'd been released, too. He pushed her toward the door and advanced on the captive, on Kaam, with his knife. She knew he would kill him. She could see the rage.

Kaam raised his free right hand without turning from the wall and his constant, rhythmic writing, and said, "Anger is not your sin, Chatar. Thank you for bringing her. Now tell her the truth."

He was writing her name now. Over and over and over, in flowing white letters on black stone. Samarjit. Samarjit. Samarjit. Like a silent chant, madness and chalk on stone.

Her father stopped. She could see his muscles twitching with the desire to act, to protect her, but he sheathed the kirpan and backed away. Then he grabbed her and hurried her out of the room, down the chalked hallways, down the stairs. She didn't care where she went now. Part of her would never leave that room.

He pulled her to a stop at the thick plastic barrier. Through it, she could see the two soldiers standing guard, and the area beyond that was the world and not the Citadel. They were in the Citadel. That was the antechamber, worlds away. She understood now that what was out there was not . . . this.

This, here, was real.

The barrier, however thick, however secure, was not strong enough to hold in Kaam. All this high-tech security was a lie told by children to master their terror. A candle against a hurricane.

Her father was breathing so hard that she feared for him. His face beneath his beard looked stark and pale.

"God forgive me," he said. "God forgive me for bringing you to him."

"He didn't hurt me." He had, but it was gone now. What was broken was healed, except for the hidden things, secret things, which would never again be whole.

"It doesn't matter. Samarjit, your name is on his wall."

"He said you'd tell me the truth. Please. Tell me—" She reached out to him, but he backed away. And on some horrible level, she understood why. She felt numb

now, and the sound of chalk scraping on stone continued relentlessly in her ears.

She felt a shudder go through the stone beneath her feet, an awful, unsteady pulse, and grabbed for the stone of the wall beside her. "What is that?"

"It's him." Her father strode to the keypad and entered his code; he hesitated before he hit the last button and looked at her with unfathomably sad eyes. "You wanted to know what I called him," he said. "You named him one of the five evils in our religion. Kaam, for lust. For me, he was Moh." Moh was attachment. All Sikhs sought to keep their passions in balance—lust, greed, pride, anger. Even attachments like love. She had always been her father's biggest struggle, because his love for her had been too great, too out of balance. "He makes us destroy ourselves, Sammy. It's the only power he has. We have to go. Now."

He put the last number in, and the plastic gates slid open.

Her father plunged through.

Sammy didn't follow.

Chatar Singh realized at the last second and turned; the full blue skirts of his chola flared as he spun around toward her, but the gates were already crashing shut between them. Soundproofed, she realized. She couldn't hear his scream. Couldn't hear the shouts of the guards as they restrained him from the keypad.

She wished she could have explained it to him. She only knew that somehow, she had no choice.

He makes you destroy yourself, her father had said, and maybe that was true. But she also understood something else, something deeper than that. We are his demons. This is his hell.

She had to try to free the captive.

* * * * *

The world shuddered again, and when she blinked, there wasn't a gate anymore. Where the gate had been was a black rock wall. The boxes of chalk were still in the room, and despite all the lurching and falling, not a single one had shifted on the shelves.

Something fundamental had shifted.

She could hear Kaam still writing, three floors up, the constant raw hiss of chalk on stone. She wondered if it was her name being written, over and over, like an incantation. It terrified her to think that it might be . . . and, she had to admit it, it thrilled her.

Sammy took the stairs two at a time, up two floors, then the third at a slower pace. Her ears led her straight to him. He'd moved again, into a pristinely clean room, and was just starting a new wall. He was lying flat on the stone floor, writing backward from right to left, and as he finished the first line, he moved up just enough to allow the letters space and began the next.

"You didn't leave with him," he said. "Sammy, that is not wise. How do you know I won't kill you?"

"Maybe you will," she said. "But I'm your demon, right? You're not mine. And as long as I stay away from you, you can't stop writing long enough to kill me. Can you?"

He tapped his right hand gently on the floor as he continued to move chalk over stone, and a bone exploded in her own hand and blew shards bloodily out from the skin, as if she'd been shot with an invisible bullet from the inside out. She screamed and clutched the hand to her chest, and blood flooded out over her shirt, sticky and hot. She almost fell.

He tapped again, and it was all gone. All fine. Her hand worked, the bones intact, skin unbroken.

She was still splashed with fresh blood.

"And now we understand each other," Kaam said. "But it's too late now, Samarjit. Too late to run from what you are."

She was shaking so hard that she sank down to a graceless sitting position, staring at him. At the movement of the chalk, drawing out words and phrases, lines and paragraphs. "What do you think I am?"

"Something new," he said. "Something extraordinary."

"Why am I extraordinary?" she asked him and settled into a crouch some feet away. He didn't turn his head.

"You stayed," he said.

"That's not really an answer."

"Oh, I have to answer to you now?"

"Yes," she said, "or I won't bring you chalk."

There was the slightest hesitation in his writing, a stutter, hardly even noticeable. "That's a stupid threat to make, Samarjit."

"It's Sammy, thanks, and I know. Answer me or no more chalk."

"You are extraordinary because I cannot answer that question."

"God, you do go in circles," she said, and laughed. She couldn't think why, because she knew she should be frightened out of her mind, desperately afraid. She had been, when she'd first seen him, but now that he had a name, Kaam, she was fascinated. She'd named him after a sin because that was what he made her think about. Sins. Sins of the body. Graceful, longed-for sins. "All right. These things you're writing. How do you know them?"

"How does anyone know anything, Sammy?" If she'd hoped that hearing her nickname instead of her full, formal one would sound less intimate on his lips, she was wrong. If anything, it was more intimate . . . as if she'd allowed him to see parts of her that were only properly meant for someone else. "I am remembering. Before it's all lost."

She wanted to ask him more about that, but she had bigger problems. "Are you what the Christians would call . . . the devil?"

He laughed. It was a pure, funny sound, contagious and joyous, and she found herself smiling when it was over. Tears glittered cool in her eyes. "No, sweet Sammy, I am not the devil. I am not God. I am not anything. That is the point. I am nothing, but this, this is everything. The act of chalk on stone. Words on the skin of the world."

"I don't understand."

"I didn't think you would. I am just answering your question."

She sat in silence for a while, watching him. He used up a stick of chalk to a nubbin, and before that crumbled into dust, he fetched another from the box with his right hand and passed it to his left to keep writing without pause. Smooth. Seamless.

Beautiful, really.

"You're going to have to let me go soon," she told him. "I'm human. I'm going to need food. Water. Bathrooms. Things like that."

"You'll find them downstairs," he said. "They're there when you need them. I don't have many visitors who want to stay, but when I do, I look after them."

She left and explored. He was right. There was a clean steel kitchen downstairs with a vast pantry stocked with food . . . and a microwave, which was good, because she was a terrible cook. The bathroom was the same black stone, sinks and shower and tub and toilet, but it was all beautiful. The towels were thick black cotton. In the bedroom she found next to it, there was a bed on a platform of black rock, with crisp white sheets. A mirror and dresser. A closet full of clothes in her size.

I am not the devil. I am not God. If he wasn't either of those things, she didn't understand him at all.

Days passed, or she thought they did; no watch, no phone, no clocks. Her father must have been driven mad with terror for her, but she didn't feel afraid. She had plenty to read, if she wanted; the walls were densely covered for ten floors with written works—entire books. Some were sacred, many more profane. Science fiction was next to Middle English texts she could barely read. Dry technical papers next to lush romances. The eighth floor was covered floor to ceiling with a mathematical proof that she finally figured out was part of a calculation of pi.

But most of the time, she found herself sitting in the room with him, kneeling close, passing him chalks. We are here to serve, her father had told her. Thousands of families took turns when the Citadel was in a place where the way was open, but for now, she thought, he only wanted to be with her. Only her. And she felt the heat between their bodies, the steady rising tide of desire.

His eyes were black—black irises, black pupils—and he never locked gazes with her again. His skin had a burnished, perfect look to it, as if it wasn't really made of human cells at all, but when their fingers brushed as she passed him chalk, he felt warm and real. She found she longed to trail a finger down that perfect skin. To see what he would do in return.

"Don't you ever rest?" she asked him, as he finished a piece of chalk and she handed him another. "Don't you have to rest?"

"There a

re many things I don't need. Food. Water. Sleep."

"You need someone to bring you chalk."

He smiled. It was too wide, too strange, and she felt a little pulse of disquiet. There were times when Kaam seemed perfectly sane, and she liked those quiet moments, but then there were times like this, when there was a wild, snapping energy inside him that frightened her. "I could make chalk appear," he said. "The ritual was meant to keep visitors coming here. I need visitors, Sammy. If I am left alone . . ."

"You close the exits. To keep me with you."

"Yes. Do you want to leave me?" It was a quiet question, but there was a kind of resignation in it, too, as if he knew she would leave him soon.

She didn't know that. When she was here, next to him, her whole body burned, tingled, soared. When he brushed his fingers on hers it took her breath away and brought tears to her eyes. Kaam made her feel more alive than she had ever known it was possible to be.

"I don't want to leave," she said, and then forced herself to laugh a little. "Although you have to put in an internet connection and a computer, or I'll go crazy eventually. And my—" Her voice died, because for the first time in a while, she thought of her parents. Of her father, saying her name as the Citadel lurched and went away. Of her mother, who hadn't known she was coming here. Were they together, united in fear and grief for their daughter? Or was her mother screaming in rage at her father for taking her here, to him? The prospect made her feel sick.

"I could tell you that your parents are fine, but that would be a lie." His voice changed, grew tight and strained. His hand began to shake, though the shapes still formed perfectly under the moving chalk. He had abandoned the musical notation he'd been writing and instead shifted to letters. Her name, over and over. "I have taken their daughter away. They can never be fine again."

"Kaam—"

"Everything fades. Everything falls. Everyone goes away." As Kaam spoke it, he wrote it. Then again, in French. In German. "Go away."

The Unlocked Tome: An Annwn Cycle Tale (The Annwn Cycle)

The Unlocked Tome: An Annwn Cycle Tale (The Annwn Cycle) The Dark Thorn

The Dark Thorn Unbound

Unbound The Twilight Dragon & Other Tales of Annwn: Preludes to The Everwinter Wraith (The Annwn Cycle)

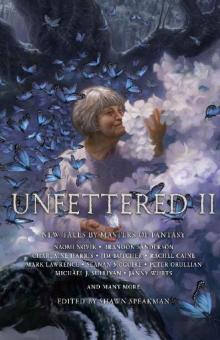

The Twilight Dragon & Other Tales of Annwn: Preludes to The Everwinter Wraith (The Annwn Cycle) Unfettered II: New Tales By Masters of Fantasy

Unfettered II: New Tales By Masters of Fantasy